Remember the year 2000? If you were around, you might recall the sheer panic that gripped the world as we approached the end of 1999. People stocked up on canned beans and bottled water like they were preparing for a zombie apocalypse. Why? Because of a little thing called the Y2K bug.

Y2K: When Computers Feared the Millennium Bug

The Y2K bug was essentially the tech world’s version of forgetting to update your calendar. For decades, programmers had been using two digits to represent the year in their code (e.g., “99” for 1999). But as 2000 approached, the fear was that computers would read “00” as 1900, throwing modern society back into the days of horse-drawn carriages and telegrams.

The world braced for impact. People joked about ATMs spitting out money like slot machines and traffic lights going disco on us. Governments and corporations spent billions to fix the issue. Midnight came, we all held our breath… and then? Well, not much happened. It was like waiting for a sneeze that never came.

Fast forward to today, and we can laugh about it. But guess what? We have another date with disaster in 2038, and this time, it’s a bit more specific: January 19, 2038, at 03:14:07 UTC, to be exact.

Y2030 (or The 2038 Problem)

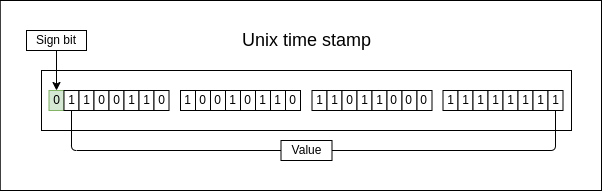

Let’s talk about Unix time. Unix systems, which underpin much of the internet, count time in seconds from January 1, 1970 (known as the Unix epoch). The trouble is, they use a 32-bit integer to store this number. This was fine once it was introduced, but as we approach 2038, that number is going to max out.

Imagine a 32-bit integer as a soda bottle. It’s been filling up, second by second, since 1970. In 2038, it’s going to overflow, and the clock will reset to something wacky, like December 13, 1901. Your smartphone might suddenly think it’s a pocket watch from the Victorian era.

Let’s see why is that. Int32 type has 32 bits, out of which the first bit is used as a sign bit and the rest are used for value. If we take the current time we can get the binary representation:

1

2

3

4

5

const date = new Date()

// Tue Jul 16 2024 22:33:03 GMT+0200

const binary = (+date/1000).toString(2) // divide by 1000, as Javascript counts milliseconds as well

// 01100110 10010110 11011000 11111111

Now imagine that we have all the ones for the value (1111…1111). Adding one more one would alternate the sign bit to 1, making this number the biggest negative integer that can be represented using the int32 type.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

"1"+"0".repeat(31)

// 1 followed by 31 zeros

-parseInt("1"+"0".repeat(31), 2)*1000

// parse that as integer and multiply by 1000 milliseconds

new Date(-parseInt("1"+"0".repeat(31), 2)*1000)

// Fri Dec 13 1901 21:45:52 GMT+0100 (Central European Standard Time)

As you can see, it effectively brings us back to 1901, which can harm data in Unix-based systems.

Solutions

Unsigned integers

Some programming languages use unsigned integers for storing dates, which gives us an additional 2^32 seconds, or more practically speaking it overflows at 2106:

1

2

new Date(parseInt("1".repeat(32), 2)*1000)

// Sun Feb 07 2106 07:28:15 GMT+0100 (Central European Standard Time)

When it overflows, it goes back to 1970-01-01.

Using 64bit number

Going to 64-bit numbers will give us a much greater range, but usually what you’ll see is that by using 64-bit Unix timestamp, is that it also takes milliseconds as well.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Math.pow(2, 64)

// 18446744073709552000

1000 /* milliseconds */ * 60 /* seconds */ * 60 /* minutes */ * 24 /* hours */ * 365 /* days */

// 31536000000

18446744073709552000 / 31536000000

// 584942417.355072

This gives us roughly 584 942 417 years since 1970 until overflow. That’s a lot.

Javascript

Here things are a bit strange, as Javascript uses Double-precision floating-point format for representing numbers. On top of that, Date is limited to a range of exactly -100 000 000 days before and 100 000 000 after 1970-01-01 (in milliseconds).

This gives us:

100_000_000*1000*60*60*24=8640000000000000 milliseconds to work with in Javascript applications.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

new Date(8640000000000000)

// Sat Sep 13 275760 02:00:00 GMT+0200 (Central European Summer Time)

new Date(-8640000000000000)

// Tue Apr 20 -271821 01:22:00 GMT+0122 (Central European Summer Time)

new Date(8640000000000001)

// Invalid Date

new Date(-8640000000000001)

// Invalid Date

Worry or not to worry?

So, should we be worried? Maybe just a smidge. While the 2038 problem isn’t expected to be the global meltdown that Y2K was supposed to be, it’s still a significant issue. Systems that aren’t updated could fail, causing everything from minor inconveniences to major disruptions.

On the bright side, programmers have had decades to learn from Y2K. If there’s one thing we’ve learned, it’s to take these warnings seriously… and to laugh a little along the way.

Why did the Unix programmer go broke in 2038?

Because their time was up!